Archive for 2013

A Street Car Named Tro-Tro, or, Twelve Months of Riding in Tro-Tros

0Saturday 9 November 2013 by Renee

It's hard to believe but we've almost been in Ghana for a whole year, which also means it's also very, very close to going home time.

The last few months have been hectic beyond belief - things got very busy at work, we finally had a chance to use our leave and see some of the rest of West Africa (definitely a few posts from those adventures to come), and two friends visited on two separate occasions which was great fun showing newbies around the crazy place called Ghana. On top of that, or perhaps as a result, my immune system also decided to take a holiday, which didn't exactly help the cause of dealing with so much to do!

There is so much more I wanted to write about here, but the blog just had to take a back seat for a while. Which, speaking of back seats, brings me to this post, which I've really wanted to share for ages as it's been such a part of life here - riding in tro-tros, the local name for the busted up mini vans, mostly dumped here from Europe, that are the main way of getting around...

Yup, mechanics are fairly resourceful here. It looks like something from a car yard, but that picture above is a picture I took in a tro-tro while I waited to for it to fill. There are no time tables, the tro-tro starts when it is full, at which point it starts it's route and the next one starts to fill. It's second nature now, but its so different to any public transport system I've ever used.

Apart from the stations where the routes start and finish, there are no marked bus stops, instead random landmarks that everyone just knows - a particular signboard, telephone pole, shop or tree, with names to match - ie "communication" for a stop that happens to be near one of many telephone poles, "barrier" for the stop near a particular police barrier (check point), "pharmacy" for a stop near a particular pharmacy. There are no signs that tell you where the tro-tro is headed, instead, the (driver's) mate, who's job it is to collect the fares, hangs out the window yelling the destination or it's abbreviation - For the centre of the city - Accra-cra-cra-cra, For Nkrumah Circle - Cir-cir-cir-cir. There are great hand signals as well.

Tro-tros are fitted out with seats to use up every space in the van, with flip up ones along the side. Which means that at least a handful of the passengers have to pile out to let a passenger sitting beside or behind them out at each stop. Most tro-tros have seats for about 16 people, but I've been in ones that have crammed up to 25 (Overload!). Keeping in mind this is the tropics we're talking about, it's nice and sticky, especially in Accra's notorious traffic where you can be at a stand still for hours on end.

The skills of the mates - many of whom are illiterate - never cease to amaze me. At some point after you're seated - sometimes half an hour afterwards, the mate will indicate to you, at which point you tell him where you're going and give him the fare, (and ask him what the far is if needed). He takes your money, and then proceeds to collect other people's money, interspersed with hanging out of the door advertising where the van is headed and helping people get on and off. At some point later in the journey, he'll give you back your change if needed. How they keep track of it all - all of the fares from every possible combination of start and end point, who has paid, how much they paid and what they are owed, is incredible.

Often, taking taxis is much easier and faster, but tro-tros are so cheap that most people prefer them - my ride to work, (after I've gotten a cab to the nearest stop to save some massive backtracking), was 80 pesewas or 40 cents in $AU terms, as opposed to a 12 cedi cab ride the whole way. They're also a great way to get a better sense of life here - everyone from fancy-looking business people, mechanics taking a chunk of a car to somewhere, police nursing their ak47s, and women taking their produce (alive and dead!) to market, all take tro-tros. Which sometimes means you end up with some great travelling companions, like the dried fish we found /smelt under the seat in front of us in the photo below...yum yum!

I'm going to miss the way everyone pitches in to help people get on and off the tro-tros, mothers will pass their children to the nearest passenger on board to hold while she gets on with her youngest on her back, and people will get off and help others with their produce. I probably won't miss the hoarse-throated preachers that pop up randomly then demand money from everyone for the pleasure before jumping off, presumably to find some more unassuming customers (this being the one of the most fervently religious countries in the world, passengers comply, creating a fairly nifty business model don't you think?) But I will miss the quotes and phrases, often religious, that adorn both tro tros and other vehicles in Ghana. Here's a couple of my favs....

Cape Coast Castle and Modern Day Slavery

0Thursday 12 September 2013 by Renee

Another flashback post, although loosely related to some more current work...

Slaves that didn't die from these conditions were kept here for months until they were processed and put on ships via the door of no return. At Cape Coast, this was the last stop before crossing the Atlantic.

And yet, even where the relics of the Transatlantic slave trade stand watch along the shoreline, the above promise remains unfulfilled. In Ghana, child trafficking is a significant issue, where most frequently children are trafficked to work in the fishing villages along the large Lake Volta . On fishing boats, children are put to work as their small hands and bodies are considered to be useful for diving to de-tangling nets caught on the plentiful submerged trees. The work is brutal and dangerous, and children also experience sexual abuse and corporal punishment from their slave masters.

Recently, I've been helping to research and develop a new project for my organisation, to use our methodology with survivors and children at-risk of child trafficking. The project aims to provide sexual and reproductive health education to the children, and to help them use drama as an advocacy tool to raise awareness amongst the broader community, in partnership with a child rights organisation.

During our orientation week (which now feels like a lifetime ago), we made a trip to Cape Coast, a few hours west to visit Cape Coast Castle. Ghana was one of the key exchange points in the Transatlantic Slave trade which operated from the 1600s to 1800s. Ghana's coastline is littered with forts and castles built by various colonial powers to store and process their slaves and ship them off to sea.

It's a haunting and stunning building; beautiful and serene, but it was almost like you could feel the hundreds of years of suffering held within it.

Cape Coast Castle was built and originally operated by the Swedes (not so neutral now huh?), seized by the Danes and then the Brits, who ran their slave trade from the castle until 1844, when it became the centre of the colonial government of the British Gold Coast until independence in 1957.

Our guide gave us an impassioned tour of the castle, including the dungeons where 200 slaves were kept at any one time in the space of about 7x4 metres. The dirt covering the cobblestone floor is actually about 30cm of blood, sweat, urine and feces accumulated over the 200 years of operation - you can only imagine the smell. The three tiny peep holes provided the light and oxygen for the slaves.

Slaves that didn't die from these conditions were kept here for months until they were processed and put on ships via the door of no return. At Cape Coast, this was the last stop before crossing the Atlantic.

Over half of the people captured died en route due to ill treatment and the diseases that ran rife through the crowded ships. Women and girls were raped by the ships crew, and their babies provided "sustainability" to the trade - the next generation of slaves in the new world.

And yet, even where the relics of the Transatlantic slave trade stand watch along the shoreline, the above promise remains unfulfilled. In Ghana, child trafficking is a significant issue, where most frequently children are trafficked to work in the fishing villages along the large Lake Volta . On fishing boats, children are put to work as their small hands and bodies are considered to be useful for diving to de-tangling nets caught on the plentiful submerged trees. The work is brutal and dangerous, and children also experience sexual abuse and corporal punishment from their slave masters.

Recently, I've been helping to research and develop a new project for my organisation, to use our methodology with survivors and children at-risk of child trafficking. The project aims to provide sexual and reproductive health education to the children, and to help them use drama as an advocacy tool to raise awareness amongst the broader community, in partnership with a child rights organisation.

In poor communities, it's common for parents, many of whom may not have planned their children, to negotiate a fee in return for their child to work in another village, or the parents may be deceived into believing that trafficker will provide schooling and perhaps a small amount of work outside of school. Often the trafficker is a family member

such as an uncle, so it's not viewed by families as trafficking. Alternatively,

traffickers or agents sometimes approach parents directly, promising their

children a better life. The issue is extremely sensitive and taboo, and the underlying issues - poverty, unplanned pregnancies, and lack of education - aren't easy issues to address.

Slavery may not technically be state-sanctioned these days, but global estimates of the number of women, men and children in slavery today range from 20.9 million (ILO) to 27 million (Free the Slaves). By comparison, best estimates of the Transatlantic Slave trade suggest approximately 12 million people were shipped as slaves (although including the numbers of deaths would include a much higher number).

Like it or not, we're all actors in a global economy, and the decisions we make about the products we buy or the services we use can help to either sustain such abhorrent practices, or demonstrate an alternative, more humane way of doing things.

If you'd like to learn more about modern day slavery, there is no shortage of coverage on the internet, but the BBC has a great overview here, and Free Slaves have a great informative website too.Slavery may not technically be state-sanctioned these days, but global estimates of the number of women, men and children in slavery today range from 20.9 million (ILO) to 27 million (Free the Slaves). By comparison, best estimates of the Transatlantic Slave trade suggest approximately 12 million people were shipped as slaves (although including the numbers of deaths would include a much higher number).

Like it or not, we're all actors in a global economy, and the decisions we make about the products we buy or the services we use can help to either sustain such abhorrent practices, or demonstrate an alternative, more humane way of doing things.

Wedding Tips from Ghana

3Thursday 1 August 2013 by Renee

This post actually relates to an experience from a few months ago - in an attempt to post more regularly and to get through the backlog I think I'm going to start having a few flashback posts now and then....

Also this was inspired by an email exchange with one of my dearest friends Brooke, who will be getting married next year. As one of the bridesmaids, I would otherwise be trying to help her and Lyndon with wedding plans, alas I'm on another continent, which often feels like another world away. It certainly feels like another world away when I try to make up for my absence by searching wedding blogs to find bridesmaid dress ideas and find hilariously overstylized nonsense such as this angel-inspired wedding. Seriously, who would do that? Because I want to punch them. ANYWAY.

So one of the recommended cultural experiences here is attending a wedding, funeral and outdooring (naming ceremony). In Ghana, and from I hear most other places in Africa, weddings don't really have the "exclusive invite" vibe that happens in the west. Which works out great, because no one bats an eyelid when their friend invites some obruni colleagues they've never met. Well that's not entirely true, but only because the presence of obrunis generally leads to a lot of excitement anywhere, rather than it being strange to invite ring-ins to weddings.

So a couple of months ago a colleague invited us to her friend's wedding, thus Adam and I got to tick one of the cultural "must-dos" off our list. I figure it's also helped tick off some of my bridesmaid duties, right Brookles? What I've summised from this and other experiences is that joy is pretty high on the priority list for Ghanaians. While their Western counterparts are wondering how to attach wings to themselves and how to get the forlorn/hipster/contrived romance balance just right, Ghanaians are asking, "How can I make this even happier?", "Is it bright enough?" and "Will people have fun?".

So ladies and gentlemen, I present to you ten hot wedding tips from Ghana:

1. Pick a nice bright colour theme like lime green, and stick to it. Voraciously.

2. No stone should be left unwrapped in this chosen colour. Not even your ushers, gifts, pillars, guests, choir, or praise choir

3. Have a praise choir

5. You can never have too many indoor garden arches, and indoor garden gazebos

7. Have at least 12 ministers/pastors, the main one being a caricature of Whoopy Goldberg, who likes to use her booming voice to say "By the lurve of Jay-sah-hus" frequently

8. Encourage the frequent use of whistles (like umpire whistles) amongst your guests. They come in handy for creating atmosphere at key points in the ceremony

9. Every song should lead to a mosh pit of dancing at the front of the church, and people dancing up and down the aisles

10. Give up on any idea of timing, running sheet etc. People will show up when they arrive, and leave when they feel they've shown their respects enough. Dancing and singing their way out. In fact, it's common for weddings to not start until three hours after the intended starting time (people will phone the bride and tell her not to come until the church is full).

Seriously though, praise choir - amazeballs. Not just singing, but randonly punctuating the service with "Ahy-mennnnn", "Alle-lujaaaaaa" and "Ahaaaahh"

7. Have at least 12 ministers/pastors, the main one being a caricature of Whoopy Goldberg, who likes to use her booming voice to say "By the lurve of Jay-sah-hus" frequently

8. Encourage the frequent use of whistles (like umpire whistles) amongst your guests. They come in handy for creating atmosphere at key points in the ceremony

9. Every song should lead to a mosh pit of dancing at the front of the church, and people dancing up and down the aisles

10. Give up on any idea of timing, running sheet etc. People will show up when they arrive, and leave when they feel they've shown their respects enough. Dancing and singing their way out. In fact, it's common for weddings to not start until three hours after the intended starting time (people will phone the bride and tell her not to come until the church is full).

Seriously though, praise choir - amazeballs. Not just singing, but randonly punctuating the service with "Ahy-mennnnn", "Alle-lujaaaaaa" and "Ahaaaahh"

Adam and I were both coming down with colds at the time, but it was still a serious amount of fun. At the end, when everyone lined up to thank/congratulate (and in our case, meet) the bride and groom, with everyone dancing while they wait their turn, my colleague reprimanded my dancing style- "Renee, we do not Azonto in the church" she said sternly. After we said our greetings, people were congregating and dancing azonto style in the space next to the bride and groom. As we went to walk through the group I casually pulled out a few moves, which had more or less the entirety of what was left of the party in hysterics - "Obruni is dancing, Obruni, can you Azonto?" - to which of course I had to pull out my best Azonto moves. Rule number one of being a foreigner in Ghana: all interactions lead to you being an azonto-dancing performing monkey.

Being Lucky

0Tuesday 18 June 2013 by Renee

Last Monday Adam and I came home from a morning jog on which we were relieved of our phones and the small amount of money were were carrying on us. An annoying experience, but we never have to look far to be reminded how good we've got it...

After spending a good half hour dissecting the event with Sammy, the gym instructor at the small gym inside our compound, he asked us if we had heard the news about our neighbour. We hadn't and asked for more detail.

While we didn't exactly know her well, Adam and I had chatted with her and her family around a fire in her front yard, across the road and down a property from our own place, one evening a couple of months ago. As I was walking home in the afternoon, I had been making small talk and quizzing her sister about the ingredients she was carrying, and ended up with a dinner invite. While it's hard to decipher between courtesy invites ("Please, you're invited") and genuine ("Please I actually want to share my food with you") invites, we decided we might as well try and make friends with the neighbours, but hedged our bets and ate first. That was a good thing as it was indeed a courtesy invite, but they were happy to chat to us for a while. Theirs was a house typical in this new part of Accra, a strangely large but incomplete shell that families camp in until they save up enough to have the next stage built. We sat on wooden benches and chatted in broken Twi and broken English, family members translating for each other, and while we missed some of the conversation, I'm certain that the pointing to my legs and the reference to the colour of cow bones were linked...

Sammy explained what had happened. The girl, maybe late teens, early twenties, had died. She was trying to give herself an abortion.

No matter your standing on abortion, it's an absolute tragedy; at every point in the series of events that led to our neighbour's death, there were actions that could have been taken to save at least one young life, and perhaps even two.

The need for sexual and reproductive health education, including family planning, is huge here. I recently read a statistic that 750,000 teens end up with unplanned pregnancies every year, and deaths from unsafe abortions account for 11% of all maternal deaths. In 2008, the risk of maternal death was a 1 in 66 chance in Ghana, while it was 1 in 7400 in Australia.

While there's a lot of poverty here, it was the first time someone's story and the broader situation had really touched me. I know things like this happen all around the world. But somehow it's so easy to think of it in abstract. In a remote location. Out of sight. Not across the road from my house.

What a way to put my new job in perspective.

Later I shared the story with my colleague at work, trying to make sense of it all. An, awful, awful tragedy, he agreed, but then enlightened me some more. People are ashamed, and don't want to talk about the issue. Then it happens to them, and they try any old wives tale they've heard - herbs, chemicals, Guinness with lots of salt, but the most common? Swallowing ground up glass. Such a violent thing to do to yourself.

"Eh! Ghana-ooo..." he said sighing and slowly shaking his head. "Do you know, you are lucky, Renee, sooo lucky. If I had my time again, I wish I could have been born in a place like Australia".

So many people here want to leave (we hear "Oburni! Take me to your country!" all the time) and my go-to response usually is to focus on the positives, the culture here, and potential for people to change their country's direction ("but chale, if all the people who think like you leave, then who will make Ghana a better place?").

But this time, I had nothing. "I do know, I'm very lucky."

What on Earth Am I doing in Ghana?

0by Renee

It’s a question I ask myself often. I never meant for this blog to be only happy-snaps and travel tales - if you only followed this blog you’d think we’d been on a seven month long holiday, which is definitely not true! From now I’ll try to rectify this. And I'll start by explaining what I'm up to.

My assignment here, was to work with a network-based NGO working in the field of sustainable agriculture and rural development. Specifically they are meant to work with networks of small-scale farmers organised into farmer based organisations, to provide education and advocacy to improve the outputs of small scale farmers, and overall, reduce rural poverty.

My job was to help with stakeholder engagement, project scoping and development, research and proposal writing. When I first started, my supervisor, the national coordinator was enthusiastic, there was so much to do, he said, activities left, right and centre. I was excited. It took me less than a month to realise that what he actually meant was, that basically nothing was happening, that the organisation was in a state of disarray, and that I was going to be busy because I, as the foreigner, was going to fix it all. I was up for a challenge, and knew it was going to be a hard slog, but this seemed a bit ridiculous.

There were no projects on the books, just one being wrapped up. Core funding - the ever-elusive, stability-providing core funding - had dropped out ten years prior. Which isn't uncommon (who want's to fund boring things like project scoping, support staff salaries, and rent?), but the organisation had never really recovered. The only remaining full-time staff was the national coordinator who spent most of his time travelling and a lovely middle aged man who cleaned and ran errands, and taught me Twi when there nothing else to do. My intended full-time counterpart was in fact a volunteer agricultural scientist who worked only during the school holidays and the finance officer had left.

You can't really blame them – with your NGO in such a state, you’d say anything you could to get in on a programme promising to place qualified, experienced Australians with your organisation for a whole year for free, wouldn’t you? And the idea of the programme I’m on*, is not just to place us in fully functional, well-oiled machines, but rather place us with organisations that are doing good work, where we can learn from them but also fill gaps and improve things in some way, so the organisation can do even better work. But with next to nothing to latch onto and improve, I just couldn't. Without the support of an ag. scientist and finance officer, I could hardly help them develop better projects and proposals, and I was left, relatively unqualified for the task, to dream up my own projects and proposals to help local farmers. I did what I could, got to develop some new skills, and managed to fit in some regional travel, but by January I decided with the manager of the volunteer programme that brought me here, that I needed to change organisations.

It wasn't an easy thing to be transferred - I had come all this way to help that particular organisation, on the premise of developing skills in sustainable agriculture/rural development, but perhaps the most difficult part was that they had been (however unrealistically) pinning their hopes on me. No matter how much you know it's in everyone's interests, saying "sorry guys, I can't be a part of this" felt an awful lot like giving up.

Nothing happens quickly in Ghana, so I had to hang in there for some time before I actually transferred assignment. But now I have been in my new organisation for two months. I'm in a similar role with a bit of monitoring and evaluation thrown into the mix, but working for an organisation that works primarily in the field of sexual and reproductive health. While Ghana has made huge improvements in HIV and AIDs rates in the past ten years, the broader issue of sexual and reproductive health and related gender equality issues persist, especially HIV and AIDs prevention. My current organisation uses interactive drama and theatre methods to educate people on these issues and to improve their confidence in making positive, healthy choices and exercising their rights - rehearsing for life, you could say.

It's a remarkably effective method. Of course there are organisational challenges, but there are some amazing projects going on and I'm enjoying the exposure to the public health scene. One project is with sex workers in one of the biggest slums in Accra, and we're about to embark on a pilot project with prisoners in prisons around Ghana. Most of my work is currently office based, but once I start collecting data for evaluations I'll get to go and meet some of our programme's participants - which is always my favourite part of research.

And what about Adam? Well despite the issue of "how can a development practitioner and a violinist pursue their careers simultaneously?" plaguing us for the best part of the last five years, it turns out he's one of the busiest people I know here! Music plays a huge role in life here. Within no time, he was in touch with musicians and was playing gigs all around town. In January he started working with the National Symphony Orchestra of Ghana (yes it exists) tutoring the string sections and playing in the section too. Although they are public servants, they are mostly self-taught and there are no auditions - if you've got an instrument and can keep up, you're in! Needless to say they all seem to appreciate having someone like Adam to tutor them over an extended length of time.

It's been a bumpy ride in ways that I hadn't expected, but I'm learning heaps, especially about how development organisations work, don't work or should work.

*Although it would be easier if I could just blurt out what programme brought me here and the organisations Iv'e been working for, our media policy would mean that every post on this blog would have to be reviewed by the media relations team. So, if you want to know more, I'm happy for you to contact me and ask away!

Wild Winneba, or, That time I went to a cross- dressing, antelope-hunting, sacrifice festival...

2Sunday 19 May 2013 by Renee

When we first arrived in Ghana, our orientation included a security briefing. When our security advisor found out that one of our crew was going to be based in Winneba, a small beach-side town about one to two hours west of Accra, he couldn't help relating everything in the briefing back to how boring little Winneba is, such is its reputation for tedium.

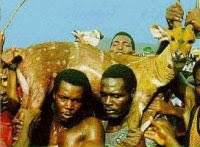

However, there is one drawcard to this quaint den of doldrums, that being Aboakyere, the annual deer hunting festival, where the Effutu of Central Coast region awake their gods and hunt antelope to sacrifice to the God Penkye Otu.

The story goes that the festival began about three hundred years ago, when a female member of the royal family was sacrificed annually to thank Penkye Otu for kindly ensuring their safe migration from the Ancient Ghana empire to the present day Ghana coast. Not suprisingly, the royal family started dying out, so the Effutu negotiated with Penkye Otu to accept a leopard instead. What were they thinking? It turns out catching a live leopard wasn't really helping the whole avoiding human death plan, so eventually Penkye Otu accepted a live antelope instead.

And that, dear readers, is how we came to be in a large field of bushes at 6am on a Saturday morning two weeks ago, surround by hundreds of Ghanaian men of all ages, dressed in women's clothing, carryings clubs and throwing around libations like it was no-one's business. We were ready to battle it out with an antelope.

By the time we had arrived, jubilating, one of the key features of the festival, was in full swing. Things had kicked off with two teams, red and white, parading around town with fetish objects like logs and whips to awaken and please the Gods. By early evening things had descended into a big street carnival, sleepy Winneba transformed into party town,with plenty of costumes, dancing and street stalls.

Jubilating carried on into the night, despite the following day's festivities beginning extremely early in the morning - locals powering through without any sleep. We were told teams start their war cries and set off into the bush around 5:30am. After a touch of jubilation we set our alarms for 5:15 and went to bed.

By 5:30am, we were ready: guys in dresses, girls in pants, but all in red, and headed out to the road to find our allies. Still dark, we found not hundreds of war-crying men as expected but four older Ghanaian gentlemen, one of them in a red ladies terry-toweling hat, but all carrying some very serious-looking clubs, and learnt that they were the extent of the team so early in the morning. Essentially, we had joined the advance party. Perhaps Friday's festivities had taken it's toll...

The journey to the Antlope-hunting site read something like the children's book "We're Going on a Bear Hunt". A four km walk through the beachside villages, along the beach, across a lagoon probably infested with Bilharzia and who knows what else, through long grass, and finally, we were in the field.

We didn't really have a plan. We knew that once an antelope was found, everyone had to run back with the antelope to the Parade Grounds 5km back in town, to present it to the cheif, who then ceremoniously steps on the antelope. Some of our crew were keen to get amongst the hunt, while others didn't want to miss out on the presentation to the chief, and others had hedged their bets and went straight to the showgrounds. We spilt, with four going off into the bushes, and seven of us planning to head back to the parade grounds to avoid having to run in the heat once the deer was caught. Good plan eh?

We had missed our chance. We found a man leading a group of younger boys all painted red, who helped us navigate the long grass. He found a clearing for the boys to sit, and ordered us to do the same. But sir, we want to go back to the showgrounds. Too late; if we went now we would confuse the proceedings. Now is the quiet time that the older men go into the bushes to locate a deer, while everyone takes up positions around the bushes, waiting for directions. Once a deer is found, then it's on for young and old, everyone making as much noise as they could to chase the deer out of he bushes, with the circle formation in theory, there to catch the deer if it escapes. We weren't going anywhere.

It turns out, that the small boys we were sitting with were very prepared for this waiting period, having brought water and snacks with them. We had neither, and having left home in the dark, hadn't eaten at all and had left sun protection at home. We also learnt that we could not cross our arms or legs, as this would stop the antelope from being caught. I'm not sure if you've ever spent a morning in a sunny field, hungry without food, in tropical heat, without sun protection or water and unable to cross your arms or legs, but I would say it's not advisable. We keep forgetting the crossing the legs thing, and people kept coming up to us, uncrossing them for us.

However, there is one drawcard to this quaint den of doldrums, that being Aboakyere, the annual deer hunting festival, where the Effutu of Central Coast region awake their gods and hunt antelope to sacrifice to the God Penkye Otu.

WITH. THEIR. BARE. HANDS.

The story goes that the festival began about three hundred years ago, when a female member of the royal family was sacrificed annually to thank Penkye Otu for kindly ensuring their safe migration from the Ancient Ghana empire to the present day Ghana coast. Not suprisingly, the royal family started dying out, so the Effutu negotiated with Penkye Otu to accept a leopard instead. What were they thinking? It turns out catching a live leopard wasn't really helping the whole avoiding human death plan, so eventually Penkye Otu accepted a live antelope instead.

And that, dear readers, is how we came to be in a large field of bushes at 6am on a Saturday morning two weeks ago, surround by hundreds of Ghanaian men of all ages, dressed in women's clothing, carryings clubs and throwing around libations like it was no-one's business. We were ready to battle it out with an antelope.

By the time we had arrived, jubilating, one of the key features of the festival, was in full swing. Things had kicked off with two teams, red and white, parading around town with fetish objects like logs and whips to awaken and please the Gods. By early evening things had descended into a big street carnival, sleepy Winneba transformed into party town,with plenty of costumes, dancing and street stalls.

Jubilating carried on into the night, despite the following day's festivities beginning extremely early in the morning - locals powering through without any sleep. We were told teams start their war cries and set off into the bush around 5:30am. After a touch of jubilation we set our alarms for 5:15 and went to bed.

By 5:30am, we were ready: guys in dresses, girls in pants, but all in red, and headed out to the road to find our allies. Still dark, we found not hundreds of war-crying men as expected but four older Ghanaian gentlemen, one of them in a red ladies terry-toweling hat, but all carrying some very serious-looking clubs, and learnt that they were the extent of the team so early in the morning. Essentially, we had joined the advance party. Perhaps Friday's festivities had taken it's toll...

The journey to the Antlope-hunting site read something like the children's book "We're Going on a Bear Hunt". A four km walk through the beachside villages, along the beach, across a lagoon probably infested with Bilharzia and who knows what else, through long grass, and finally, we were in the field.

We didn't really have a plan. We knew that once an antelope was found, everyone had to run back with the antelope to the Parade Grounds 5km back in town, to present it to the cheif, who then ceremoniously steps on the antelope. Some of our crew were keen to get amongst the hunt, while others didn't want to miss out on the presentation to the chief, and others had hedged their bets and went straight to the showgrounds. We spilt, with four going off into the bushes, and seven of us planning to head back to the parade grounds to avoid having to run in the heat once the deer was caught. Good plan eh?

We had missed our chance. We found a man leading a group of younger boys all painted red, who helped us navigate the long grass. He found a clearing for the boys to sit, and ordered us to do the same. But sir, we want to go back to the showgrounds. Too late; if we went now we would confuse the proceedings. Now is the quiet time that the older men go into the bushes to locate a deer, while everyone takes up positions around the bushes, waiting for directions. Once a deer is found, then it's on for young and old, everyone making as much noise as they could to chase the deer out of he bushes, with the circle formation in theory, there to catch the deer if it escapes. We weren't going anywhere.

It turns out, that the small boys we were sitting with were very prepared for this waiting period, having brought water and snacks with them. We had neither, and having left home in the dark, hadn't eaten at all and had left sun protection at home. We also learnt that we could not cross our arms or legs, as this would stop the antelope from being caught. I'm not sure if you've ever spent a morning in a sunny field, hungry without food, in tropical heat, without sun protection or water and unable to cross your arms or legs, but I would say it's not advisable. We keep forgetting the crossing the legs thing, and people kept coming up to us, uncrossing them for us.

Needless to say it was a long morning. Just relax, we were told. If you don't relax, the deer won't come. Ok. So some of us got comfortable, lying down in the grass. Obruni, don't lie down, you must sit! There were a lot of rules to follow, but everyone was understanding of us silly, ignorant obruni and happy to explain. As we sat, more and more boys and men came along to join us in the field, until there were literally hundred of boys and men, dressed in women's clothing, covered in red mud or red or yellow paint. The white team took the other half of the field, out of our view.

At the same time, our hunting friends were getting amongst it in the bushes, the one girl Jackie being the only female amongst them. Women aren't permitted to cross the lagoon when they're menstruating, and while in previous years some women join the hunting, as the deer have gotten harder to catch, they've more or less just banned women from joining in case they lie. As a result, Jackie had more Ghanaian men asking if she was menstruating than anyone has probably ever had in their life. Obviously, the inability of men to catch a deer is the fault of women's natural cycle, right?

Meanwhile in the field, we waited, and waited and waited. Legs uncrossed.

Then the whistles and drums and horns and screaming started, and those in the bushes started moving around the outside. And then in the field, responding to a cue none of us saw or heard, there was movement...

After a a good three hours, and one false alarm - they did catch one deer but it was too small - we decided that if a deer was going to be caught, we might as well head back, get some food, and then make our way to the parade grounds. So off we headed, through the fields, grass and even larger, muddier part of the swamp, this time with added oysters to makes things interesting, back to the hostel.

When we got home, we heard news from our hunting friends, still in the bushes that both teams were conceding defeat. This year, there would be no sacrifice for Penkye Otu.

When we got home, we heard news from our hunting friends, still in the bushes that both teams were conceding defeat. This year, there would be no sacrifice for Penkye Otu.

After some food, showering and rest, we headed into to town to see how everyone was reacting to this news.

As we soon learnt, the lack of a catch didn't really seem to bother anyone, with festivities building and crowds growing. The the second day of jubilation starting with the teams parading around town led by their fetish priests, with the rest of the town in toe.

Things have been known in the past to get a bit ugly, and there was talk about the possibility of some violence emerging at this year's festival, hence this year's theme, "Peace and Unity". All celebrations took place very peacefuly, but luckily, Ghana Police were there just in case...

As the sun went down and parade scattered, things morphed into a huge street party. In what seems to be very typical Ghanaian style, the fact that the day was more or less a failure seemed to be quickly forgotten, and everyone got on with the business of some serious jubilation, the streets packed full of azonto dancing, performances, and one cedi Star beer on tap. We were happy to oblige.

Powered by Blogger.

Labels